‘Shocking’ results from a major astronomical study have raised doubts about the standard model of cosmology, forcing scientists to consider new ways of understanding dark energy and gravity

By Alex Wilkins

2 May 2025

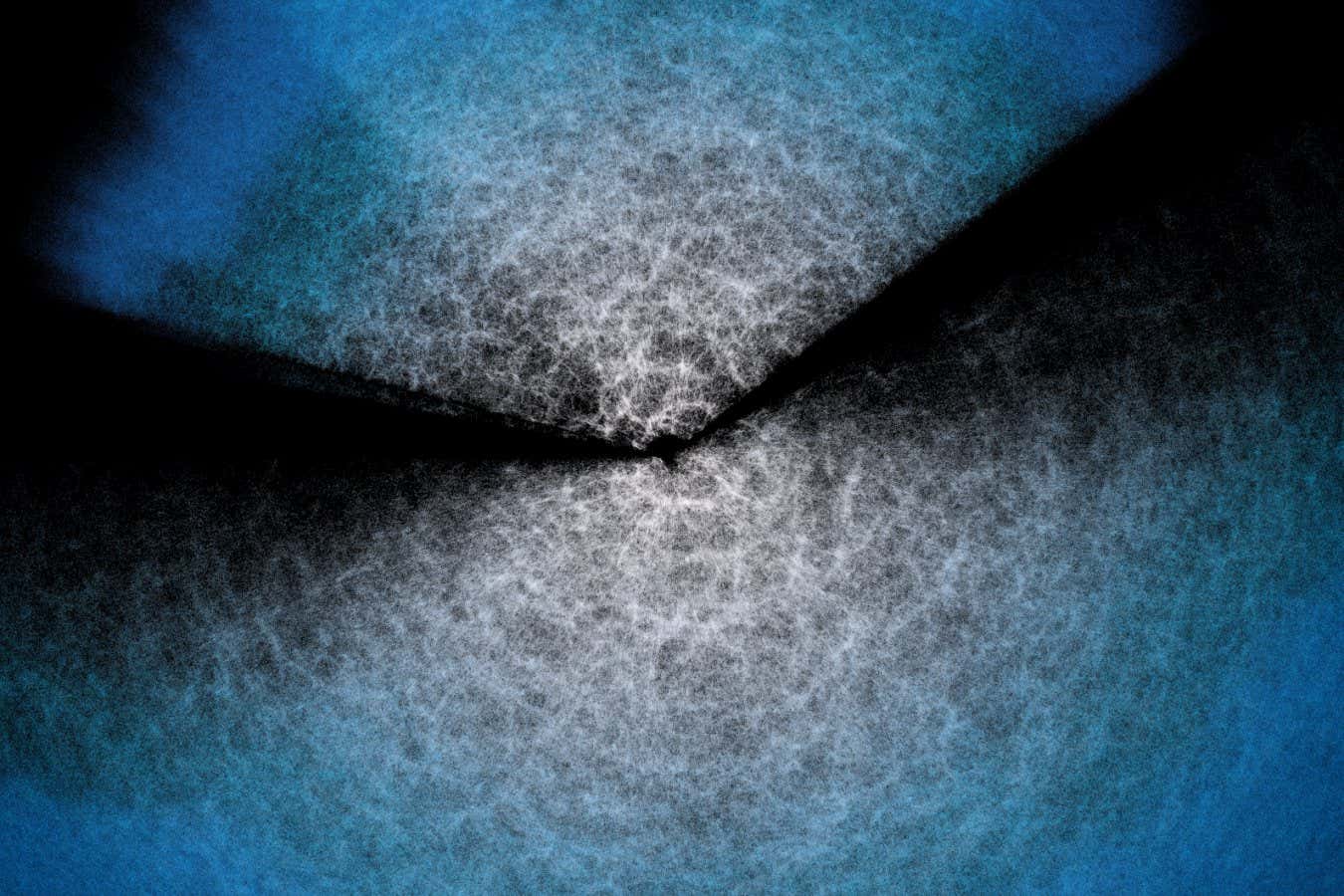

A map of the universe created by the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI). Each dot is a galaxy, with Earth in the centre

DESI collaboration and KPNO/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA/R. Proctor

In the wake of bombshell findings that suggest dark energy might be weakening as the universe expands, physicists are considering replacing the standard cosmological model of the universe with exotic new theories that say gravity works differently to how we thought. Ideas involving string theory, a new fundamental force or even a form of gravity that changes over time are all options on the table.

Our best model of the universe is called lambda-cold dark matter (LCDM), which splits the cosmos into three parts: the matter we can see, the matter we can’t see that still has a gravitational pull – known as dark matter – and dark energy, a persistent repulsive element that is forcing the universe to expand increasingly quickly. In equations first devised by Albert Einstein, the acceleration of the universe is thought to have a fixed rate known as the cosmological constant, represented by the Greek letter lambda.

Read more

One of the biggest mysteries of cosmology may finally be solved

This fits almost all of our observations of the universe so far, but the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI) in Arizona, which has built the largest 3D map of the cosmos by tracking millions of galaxies across the sky, has called the model into question. DESI precisely measures the distances between galaxies at different times in the universe’s history, allowing cosmologists to calculate how quickly the universe is expanding.

Last year, it found the first hints that dark energy isn’t a constant and that the universe may be accelerating less quickly over time. These initial results were tentative, but a second release of DESI findings in March, covering three years’ worth of data, strengthened those hints, though it still fell short of the required statistical certainty needed for a conclusive discovery. “Everybody was watching this data release from DESI, and it was pretty shocking,” says Yi-Fu Cai at the University of Science and Technology of China.

“This is exciting – it might actually be putting the standard model of cosmology in danger,” says Yashar Akrami at the Autonomous University of Madrid in Spain.